Unfortunately, my kid brother gave away my war trophy to a friend several years later.

My book was completed several years ago, but I had believed that publishing it while living was like opening up a portal to my soul and that some of the stories and events would cause me an undeserved loss of pride and dignity based on my drug and excessive alcohol use during my 49 months of combat service. Upon being hospitalized with two fractured vertebrae in 2017, another spinal surgery in 2018, Covid in 2020 and pneumonia the following year, pride and dignity took a back seat. My fear was not of dying but of dying without my book being released and the years of work putting together my book would die with me. Thankfully, I survived both spinal surgeries and the Covid and pneumonia episodes. My book is now on the web. I can die now – but my wife won’t let me !!!

Some years ago, I pulled out my remaining Vietnam mementos, a bundle of long-forgotten pictures, a small Durham’s tobacco bag of souvenir shrapnel pieces and a handful of murky, repressed and miserable memories. As I began reliving my Vietnam and Laos experiences, I found that the more I wrote, the more I recalled and the more depression engulfed me. Names, dates, particularly fascinating memories came back to me. Some I chose to write about. Those never meant to be revived have been excluded – for the moment.

Recurring stream of persisting thoughts, memories and stories are all included in some form or fashion in the context of my book. But my original draft and my bag of mementos were lost during the final stages of a divorce about 2004. In my bag of mementos were mortar and rocket shrapnel pieces I had dug out of the plywood walls of my hooches1 while with advisory teams and with 101st Airborne.

I've always viewed marriage as a business venture. When a business (marriage) fails, it's time to close up shop and file for bankruptcy (divorce), regroup, and seek out a new prospective business (marriage) partner. I walked out of my failed marriages with just my truck, a few floppy disks, my box of irreplaceable military documents and my clothes.

On 5 June 2011, I again began the process of piecing together my story from bits and pieces of printed and electronic blurbs from my original draft. The end result of my efforts follows. My book provides narrative snapshots of activities, events and tragedies experienced or observed. Consider it the documenting of a personal journal while doing a balancing act with the grief, sadness, the turbulent heart and those two wolves in my heart. No cheery endings – just excerpts about real-life moments at their best and worst in a combat environment AND a number of humorous real-life episodes to soften the dark side of combat.

It was the sixties, and the military draft was in full swing. Some were draft-exempted for a number of reasons. College enrollment was the primary deferment for those with academic ability and financial resources. The rest were quickly drafted into the military, given a job specialty and just as quickly deployed to Vietnam. I was pretty much coerced into enlisting after being called up for an induction physical. After my physical, I was classified draft status 1A and given two weeks to enlist; otherwise, I would be drafted. I did not want to end up in combat arms, so just a couple of days before being drafted, I enlisted ending up at the Fort Benjamin Harrison Adjutant General School in Indianapolis to train as a Stenographer.

I was not a good match for the military. By nature, I am quick-tempered, somewhat confrontational, argumentative and inflexible with little regard for authority – the extreme opposite of what the military demands. Though I was never a good fit for it, I did well in the US Army.

During a nine-month break from military service, I attended Del Mar College in Corpus Christi, Texas, but left after the first semester when I was accepted into the Texas Department of Public Safety Academy in Austin, Texas. Circumstances developed which prompted me to resign from the academy and re-enlist into the US Army. I grudgingly and with much trepidation made it a twenty-year career. The military was good to me, and I am indebted to it for having provided me with both a good career and an excellent education; yet, for most of my twenty years of service, I despised the military and cursed it every waking moment. I never cared for its regimented style of management, its physical requirements which ruined my back and my knees and the changing of duty stations as often as every twelve months and frequently to remote and sometimes desolate regions of the world where life was very much a hardship. Despite not being a good fit for it and despite my deep-rooted hatred for the military, I did well during my years of army service by seeking out and capitalizing on opportunities. After twenty nearly inglorious years, I retired as a Chief Warrant Officer with a Bachelors in Business Management from University of Maryland and a Master’s in Public Administration from Troy University soon after.

In my first deployment to Vietnam, I served as classified records custodian at US Army Vietnam Signal (USARV) in Tan Son Nhut. Upon completing my tour with USARV, I joined Advisory Team 99 at Duc Hoa supporting the 25th Vietnamese Infantry Division where I served as clerk and as psychological operations tech dropping Chieu Hoi (surrender) leaflets2 from an O1E Birddog flying over enemy dominated territory. Periodically we would catch ground fire then quickly abort the mission to return back to our Advisory Team 99 where the holes were patched up and the Birddog made ready for that next mission.

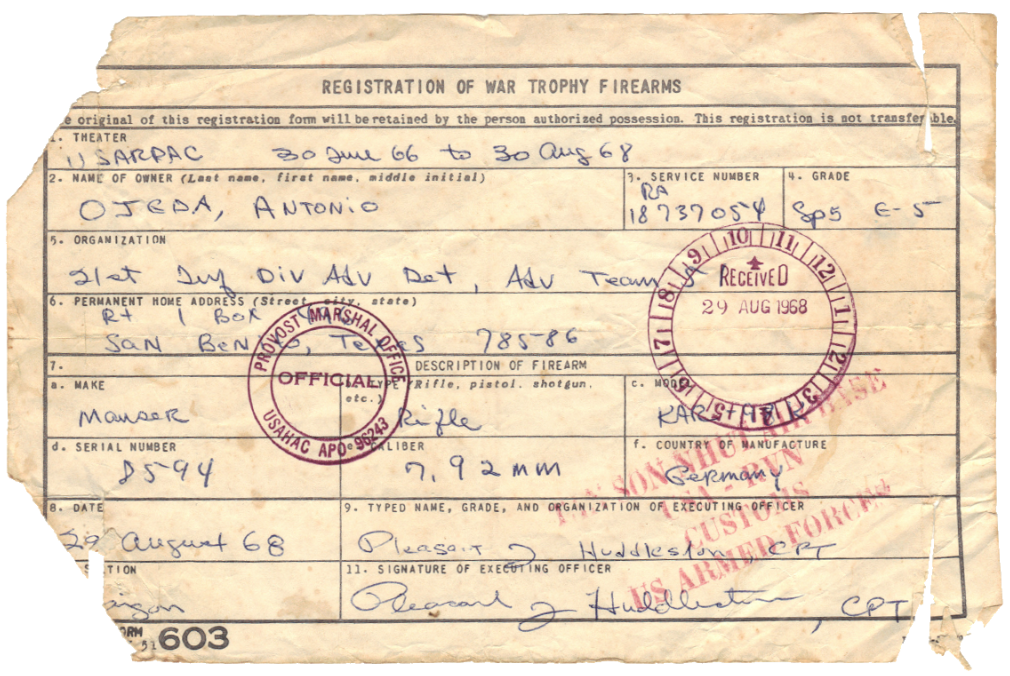

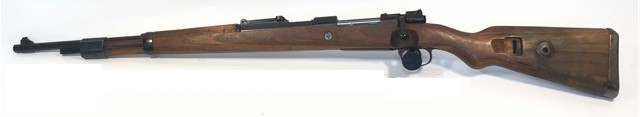

Once I completed my obligation with Advisory Team 99 and seeking reassignment to a less hostile environment, I traded two cases of cheap beer for the only available assignment in the Mekong Delta and landed at Bac Lieu some time in 1968 with assignment to Advisory Team 51 supporting the 21st Vietnamese Infantry Division. Since there were no administrative vacancies in Advisory Team 51, I switched between unfilled positions to include sergeant of the guard, radio operator, air traffic controller and PX/warehouse manager. It was during one of these assignments while on an operation that I got my captured Mauser war trophy which I brought home as a present to my kid brother, Raul, upon returning back home to Texas.

Unfortunately, my kid brother gave away my war trophy to a friend several years later.

Upon rejoining the army after a nine-month break, the Army Security Agency2 recruited and retrained me into communications-electronics then sent me to my third Vietnam tour. The Army Security Agency was somewhat of a hidden army within the US Army. Everyone in the Agency had scored in the top percentile of the induction battery of tests and was granted a Top-Secret clearance after undergoing extensive background investigations. Captain Mosely who gave me the Army Security Agency recruitment brief ended with “Our qualifications are a hell of a lot more stringent than those of even the CIA, so don’t take this offer too lightly. Trust me. You’ll want to join us.” I did.

Under the Agency banner and after qualifying the Agency’s courses in electronics and speech security devices, I joined a handful of Field Radio Repairmen with the 101st Airborne Division at Camp Eagle, Camp Evans and a number of I-Corps firebases in the northern region of Vietnam. Our mission was to intercept enemy voice and Morse code communications which the 101st Airborne then used for maneuvering and for defensive and offensive strategies. In The Sentinel and the Shooter, Douglas Bonnot captures a period of my Vietnam experience while with the 101st Airborne Division. In his book Doug documents the structuring and success of a program I initiated and managed to modify captured enemy radios which our radio voice and Morse code intercept teams used for capturing enemy over-the-air military intelligence. Doug would bring me the captured enemy radios. I would take them apart, make necessary repairs and convert their battery operation adapting them to our own military batteries.

Having been well-trained in electronics and speech security devices by the Army Security Agency led me to specialized training in Test Measurement and Diagnostics Equipment and in Firefinder target acquisition radar systems several years later. This specialized training enhanced my military career and afforded me a future career on military contracts after active duty retirement.

My last combat tour was a thirteen-month covert and sanitized civilian assignment with Project 404, U.S. Embassy in the Kingdom of Laos. I was not allowed to use military uniforms or carry US military weapons and spent my thirteen months in civilian attire with no trace of being an active-duty US Army member. The official and primary mission of Project 404 as I understood it back then was to support and train the Lao air force pilots and support personnel. The Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese army were dominant in the rural areas of Laos, and American-trained Lao pilots flew T-28s2 providing aerial support to General Van Pao’s CIA-sponsored forces. Bringing the fight to the Pathet Lao in rural areas was an orchestrated plan cloaked in secrecy with Project 404 providing the civilian-attired military personnel to that effort.

A doubly covert mission more heavily cloaked in secrecy was finding and rescuing American pilots shot down over the Kingdom of Laos. If shot down over North Vietnam air space, American pilots on their bombing missions to and from North Vietnam would make every effort to reach Laotian airspace and eject over the Kingdom of Laos. Our project would then make every reasonable attempt to locate and rescue the downed pilots. Pilots shot down closer to the Gulf of Tonkin would eject over the Gulf where Navy helicopters would pick them up and return them back to fight yet another day.

While I believed back then that our pilot rescue effort was a largely successful program, my research in the last couple of years discloses sad statistics proving our pilot rescue program was not as aggressive as I had been led to believe. Documents unclassified in the last few years state that some twenty-seven Americans were captured in Laos. Additional documents provide information that over four hundred fifty-four Americans in Laos were listed as missing in action or killed in action. Information was not easily obtained even in operations in which I participated. Typical in any classified mission, information was compartmentalized and acquired on a need-to-know basis. In the last few years, some documents regarding the Laos operations have been declassified and are available online. The murky, shadowy bits and pieces of information I picked up during my service with Project 404 are becoming more lucid with declassified information made available only in the recent last few years.

I always considered my years of military service as a career development tube, and I was to reap benefits at some future point of my life if only I persevered. Fortunately, I made it through the twenty-year tube, and my perseverance yielded me a magnificent skills set, a great education, a fabulous future career in both foreign and stateside Department of Defense contracts and a robust retirement package I could not have envisioned.

1 Hooches were our sleeping quarters made of half plywood and half screen all around. Roof was corrugated metal.

2 On 1 January 1977, ASA was redesignated as U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM).

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022