Rodriguez from Seguin, Moreno from Kingsville and I all graduated from an administrative clerk course at Ft Polk, Louisiana, in the top five percent of our class and were selected for stenography training at Fort Ben Harrison, Indiana. None of us knew what a stenographer was. I researched it at the base library and reported back to our Mexican connection that we would be learning shorthand. Rodriguez announced to the group, No, ese! Yo no voy a ser una pinche secretaria. Esa chamba no es para me.

1

We were driven to the train station in Leesville, Louisiana, where we boarded the train and arrived in Indianapolis in January 1966, in the midst of one of the heaviest snowstorms. That was the first time in my life I had seen snow. We inquired at the train depot and learned the Army liaison was only a few blocks from the depot, so we decided to walk the distance and save a few dollars since a Private’s pay back then was only seventy-eight dollars a month and paid only once a month.

It was miserably cold, and we were each carrying our duffel bags. Moreno kept complaining that it was just too cold. He was the only one without an overcoat. Moreno was short and small frame. He had not been issued an overcoat at Ft Polk because his size was not available at the time, but he was assured he could get one at Fort Ben Harrison. Once we reached the Army liaison office, we were transported to Uncle Ben’s Rest Home, a nickname by which Fort Ben Harrison was fondly referred to. Uncle Ben’s Rest Home was the epitome of what I had always wished the army to be. It was much like a college campus with the most modern classrooms, informal classes, no physical training and a communal mess facility with four serving lines. Dress greens with ties were the required uniform. I could learn to love this army,

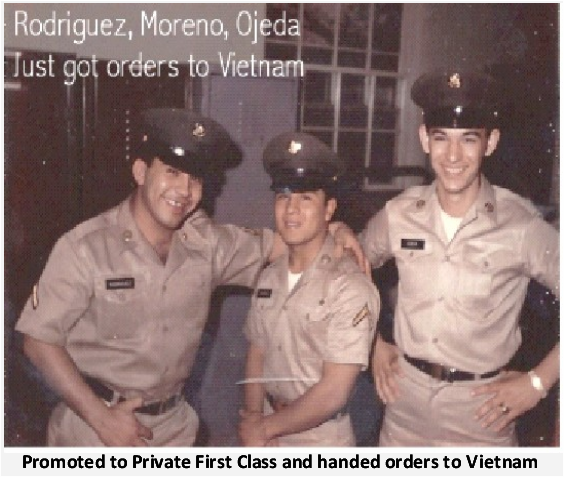

I told myself. But my world was sadly crushed just prior to completing the six-month course when Rodriguez, Moreno and I were all promoted to Private First Class and handed orders to Vietnam.

Towards the end of June 1966, we three departed Uncle Ben’s Rest Home for our two-week leave in Texas. While home in Texas, I kept watching the evening news with stories of mounting casualties in Vietnam. We had several indoctrination briefings while at Ft Ben Harrison alerting us that just because we were trained stenographers did not exclude us from seeing combat firsthand. In essence, we were soldiers first and stenographers second. This instilled in me the pessimistic attitude to prepare for the worse then settle for anything short of that. After an unremarkable two-week leave at home which ended much too soon, I departed for Oakland Army Base where I again rejoined Moreno and Rodriguez.

We must have been at Oakland Army Base for seventy-two hours at most. The processing station itself was a well-organized beehive of activity operating on a twenty-four-hour basis processing Vietnam returnees and those shipping out destined to become Vietnam replacements. There was just enough time for required orientation films and briefings, rechecking everyone’s shot record and giving us whichever shots were prescribed for duty in Vietnam.

Every single soldier received a minimum of one or two shots. Moreno was in another line next to mine. Once he got his shots, he walked past me grinning and gloating. "Solo necesitaba una, Ojeda," he told me. The medic servicing my lane informed me I needed four shots. Damn ! I got in the wrong fucking line !

I blurted out. Not to worry, Private. You need only four shots today,

the medic said. Which arm you want them in?

Let's do two on left and two on right,

I answered as I pulled up the sleeves on my tee-shirt.

Look away, then, he ordered.

I felt a bit of a sting on my left arm then turned to get my other two shots on my right arm.

Next !

the medic yelled out.

What about the other two on my right arm?

I corrected him.

You got'em all on left arm. Next !

I did not question his reply. I just moved on before he could change his mind. The guy who was in line behind me followed me saying, Damn, I can't believe he gave you four shots in the same arm and at the same time!

Since that time, I have ALWAYS looked at anyone giving me injections.

There were voluminous redundant and frivolous administrative forms to complete to include next-of-kin forms which were checked by a clerk for accuracy and passed to a senior sergeant for approval. I was sitting with some six friends around a small TV provided for us when I heard the senior sergeant yell out for O-jay-da.

Orale, Ojeda, te están llamando,

2 someone in the group said. I walked over to the senior sergeant not really knowing what to expect.

Are you O-jay-da?

he asked. I answered in the affirmative thinking just how amazing it was that I was the only one of some 250-plus soldiers to be singled out. Why me?

He roared out at me, Are you a goddamn communist?

I answered in the negative.

Then why the hell did you fuck up my goddamn list of subversive organizations?

he cruelly asked.

The Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) was about a page and a half of organizations considered subversive by the US government. After screening the list, the one question on the bottom of the second page asked, "Have you qualified the List of Subversive Organizations?" Not understanding the army’s twisted version of "qualified", I had incorrectly checked the "Yes" box.

I informed the kind senior sergeant I had thought "qualified" meant "completed" and that I had completed it as instructed.

With him yelling at me in front of a couple of hundred others who properly answered the question, I now felt a powerful need to defend myself. I started to speak when a friend grabbed my arm and cautioned me to move on. "Callate, Ojeda. El esta loco. Tiene malas tripas."3 I grabbed a new form from the kind sergeant, checked the 'No' box, signed it and handed it back to him as he glared at me.

A large stenciled sign on a wall identified several uniform items we would not need in Vietnam. We would pull the required items out of our duffle bags and throw them into the respective labeled bins. Our group lined up in another corner of our cell where we were issued a new duffle bag. As we moved along a set of stocked shelves, a supply clerk would throw a new item of issue at us then moved on to the next shelf until we completed the process. Our second duffle bag was now filled with uniform items and equipment we would be using in Vietnam.

The facility was an enormously long warehouse building broken up into separate units perhaps a hundred feet wide by a hundred feet long. At the center of each adjoining wall throughout the long building was a massive sliding door which would close with a deafening, solid thump as the two hundred and fifty or so man group was assigned to that unit. Once the sliding door closed, the group was given an identity, and every administrative action was completed as a group.

We were assigned time slots to the facility mess hall to eat as a group; however, the times were not always convenient. We might be eating breakfast at 2:00 AM or lunch at 8:00 PM. Meal times were a moving target according to the processing and shipping schedules. Some in the group lamented how this processing and movement of soldiers seemed much like a war-feeding machine. As casualties in battle occurred or as fellow soldiers returned from duty in Vietnam, another batch of replacements was fed into the war machine by way of these sectioned-off warehouse units.

The individual units were void of any furniture or decoration but for a small TV with rabbit ear antenna which had to be repositioned periodically. An enterprising member of our group got some aluminum foil from one of his mess hall trips. He fashioned about a six-inch extension to the rabbit ear antenna then boasted how much better the reception was. I failed to see improvement. A number of folding chairs, a coffee pot and a latrine with showers were set up in a small corner of the unit. The showers were equipped with some six showerheads to share communally. Half of the six or eight commodes faced each other without any privacy walls or dividers between commodes. The rest of the unit contained bunks with mattresses but no other bedding or pillows. As a group shipped out from the processing station at the end of the warehouse building, all other groups were moved one unit closer to the ship-out point.

Ok, men. Gather your shit and get ready to move!

was the order roared out to us in preparation for the move. Once that next unit was emptied out, our move began. It took all of ten to fifteen minutes. Another group of men then occupied the unit we just left. As each sliding door to that next unit shut behind us, we were one less door away from the ship-out point to Vietnam.

After a typically disastrous evening meal on our third day at Oakland Army Base, we were ordered to empty the last warehouse unit and hustled on board waiting Continental Trailways charter buses transporting us to Travis Air Base for our flight to Vietnam. I was in the lead bus tired, bored, hungry, sleepy and just plain miserable at the beginning of what was to be the next biggest adventure of my life. After about an hour on board with the buses running to keep us cool, we were allowed to get off the bus in groups of ten to take a smoke and bathroom break. When we loaded back onto the bus, two Specialist Fours boarded our bus and began passing out sack lunches. Typically Army, the unpleasant, regrettable sandwich was hard bread with a thick slice of cold dry roast beef and without a trace of mayo or cheese. Each sack contained a fruit drink and either an apple or an orange. I traded my orange for an apple and the hard sandwich for a second apple.

Somewhere after dark a sergeant jumped on board, made a final headcount, gave a packet of our orders to the major who was to be our flight commander, saluted and wished us all a good tour of duty ending with a, Now you all be safe over there and come back home in one piece.

I wondered then just how many times this sergeant had given this same curt speech. He jumped off the bus, the hydraulic doors hissed and began closing ever so slowly as the bus started pulling away in a rocking motion as it avoided potholes on the road leading away from Oakland Army Base.

My last thought upon leaving the Oakland Army Base front gate was wondering just how many of us would return that following year to come back through that front gate. Those destined not to come back through the Oakland Army Base front gate would be returning through Dover Air Force Base in Delaware which housed the military mortuary facility for the remains of Vietnam casualties. I knew this from the threats of several instructors during basic training who always warned "Either you stay alert and follow what we’ve taught you here or sure as shit you’ll be gracing the sacred walls of that goddamn facility at Dover before you even fucking know it!"

Oakland Army Base was now behind us. For those of us not destined to return safely, this was to be the last stateside military unit they would ever set foot on. (Many years later a friend I had met in graduate school was to become commander of Oakland Army Base. He invited me to visit promising he would give me a tour of my former nemesis. I declined.)

There was not much of a reaction from the men on the way to Travis Air Force Base. Most of them dozed off for the nearly two-hour trip. We spent little time on the ground at Travis. The major had a senior sergeant take charge of the group and kept us together for the hour-long stay. Once our flight was announced, we had a roll call and processed through the gate as our name was called.

I chose a window seat so I could sleep for the long flight ahead to Vietnam by way of Alaska, Hawaii and Philippines. We had to deplane at Anchorage during the refueling. It was in the wee hours of the morning, and I was tired, depressed and somewhat scared after the stories I had heard from returning Vietnam veterans. I went off by myself and just walked the corridors of that nearly empty airport. I found an unlocked exterior door and decided I just had to plant my feet on Alaska soil. Finding nothing more than cement, I walked back and joined the group as our flight was being called.

I got on an emotional roller coaster upon leaving Clarke Air Base in Philippines. I lamented my predicament getting closer to Vietnam and being unable to change the consequences. How the hell did I get myself into this, and why did these damn politicians get us into this damn mess?

I kept asking myself. I was scared, but gradually began the process of accepting whatever fate awaited me thinking the odds were on my side. Tens of thousands of men had gone to Vietnam before me, and most of them had made it back out. For some strange and unknown reason, I also took some comfort in Nunez's rebuke to Ziegler, "So we all go to Vietnam and then we fucking die! No big gig!"

1 "No, man! I'm not going to be a damn secretary. That job is not for me."

2 "Listen up, Ojeda, they're calling you."

3 "Be quiet, Ojeda. He's crazy. He's got bad guts."

. . . On the LBJ Conundrum

The major initiative in the Lyndon Johnson presidency was the Vietnam War. By 1968, the United States had 548,000 troops in Vietnam and had already lost 30,000 Americans there. "I can't get out, I can't finish it with what I have got. So what the hell do I do?" he lamented to Lady Bird." - Kent Germany, PhD - University of South Carolina history professor

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022