We arrived in Tan Son Nhut Airbase on the outskirts of Saigon in mid-June 1966 and were quickly whisked off to Camp Alpha at the far end of the airbase. My twelve-month Vietnam tour had begun. My remaining in-country days left in Vietnam was now 364. As did everyone else and for the remaining of my tour in Vietnam, I knew exactly the number of in-country days I had left on any given day. Everyone kept track of their days. When they reached the 99th day, they became the "2-digit midget" and a "1-digit midget" upon reaching the 9th day. Should anyone ask a 2-digit midget just how many more days they had left, the standard response was "98 days and a wake-up". This continued until that glorious day when my "freedom bird just got here to take me home."

Camp Alpha was the Army’s replacement depot for incoming personnel. Army units throughout Vietnam would send their personnel requirements to Camp Alpha where personnel clerks would match incoming personnel to the job specialty requirement. We had daily formations at 0800 hours and again at 1300 hours.

A senior sergeant on a raised platform would call out names of those being reassigned and their new unit of assignment. No one was allowed off Camp Alpha except those leaving for their new unit of assignment. While at times it was a furiously chaotic process, for the most part it was a well-managed operation with replacement soldiers arriving from the States in mid-morning and again in mid-afternoon and newly reassigned personnel shipping out after both morning and afternoon formations.

“Goddamit!” the sergeant atop the raised platform yelled out to a Specialist Four standing by the platform “You gave me the wrong fucking manifest AGAIN! Go get me the right this time, and hurry your ass up! You've got a couple of hundred men waiting on you!”

The Specialist Four rushed back to the orderly room to retrieve an updated list as the sergeant yelled out to us, Take a break in place while we get this shit sorted out! Smoke them if you got them. Borrow them if you don't!” In mere minutes the Specialist Four hustled back to the platform and handed the sergeant a new and corrected manifest. The sergeant regained his composure and ordered us to put our cigarettes out.

"Now, you all don't go and litter these hallowed grounds with your cigarette butts. Mail'em home or put them in your pockets! he commanded. He then began barking off the names of soldiers with their new units of assignment. If our names were not called, we were subject to a number of menial jobs painting hooches, replacing deteriorating sandbags on the defensive perimeter walls, enhancing area beautification or just picking up trash and cigarette butts. Moreno and I noticed a Puerto Rican staff sergeant who was quietly gathering all Hispanics he could find. He already had a group of some eight Hispanics. Moreno, Rodriguez and I joined the Hispanics. The staff sergeant seemed pretty official carrying a clipboard and marching our ten or eleven men detail in step while calling cadence.

Once our Hispanic formation was a good distance from the main formation, the staff sergeant dismissed us telling us in Spanish “Now, if anybody asks you, tell them you are on my work detail. We’re going to keep doing this after every formation until I get shipped out. Comprenden ?” To a man, we all “comprended”. I learned from a fellow Hispanic the staff sergeant was gathering up Hispanics to keep us from getting assigned to a work detail. After dismissal we would just go back to our hooches until the following formation. We kept up the ruse without ever getting picked for any work details. Moreno, Rodriguez and I shipped out a couple of days later.

There was clear fear and apprehension during these formations of our two or three hundred men since assignments were pretty much luck-of-the-draw. The sergeant on the raised platform would call out a group of names over an intercom "Okay, those names I just called out, go grab your bags and report to staging area one. You are assigned to 9th Infantry Division." A great 'Awwwwwww' would go up in chorus. Another group of some twenty or more names would be called out. "Okay, those names I just called out, go grab your bags and report to staging area two. You are assigned to 101st Airborne Division." A bigger 'Awwwwww' in chorus would go up. This went on for units such as 25th Infantry Division, MACV Advisory Teams, 4th Infantry Division, 173rd Airborne Brigade, II Field Force, and on and on. The longer it took to get our new unit, the more apprehensive we got and the more warm beer we drank. One quickly adapts and learns to drink warm beer out of necessity.

A few more names were called out that next day to include Rodriguez from Seguin. Rod and his group wound up going to the 1st Cavalry Division in the Central Highlands. We had lost Rodriguez leaving Moreno and myself. I had a premonition I would never again see Rodriguez.

"Orale, Ojeda," Moreno suggested. "A la mejor estos pendajos se olvidaron de nosotros."1 At the 1300 hours formation that next day, Moreno's and my name were called in a small group of some six men. We expected the worse but were both glad to find we were assigned to Headquarters, US Army Vietnam (USARV) right there in Tan Son Nhut. A loud chorus of “Yeahhhhhhhhh” went up from the cheering squad. USARV headquarters was still in a fluid state of structuring and organization when Moreno and I arrived at Tent City B, home of the USARV headquarters. I was assigned to the Signal Section supporting Brigadier Robert Terry who was both the USARV Signal Officer and commander of the 1st Signal Brigade. He split his command time between the two organizations.

Moreno was assigned as a clerk with the Department of Research and Development. Never once in the twelve months we spent there did either of us take a single dictation in shorthand. Amazingly, the Army had spent twenty-two weeks and tens of thousands of dollars training us as stenographers without us ever using the specialized training. I spent the larger part of my tour there as classified records custodian maintaining Confidential to Top Secret documents originated by or used by our Signal Section. Every major after-action report from the field came to me normally in Secret and sometimes Top-Secret classifications.

Every morning I would report to the headquarters classified section and pick up any classified documents for our Signal Section. I would inventory the pages of each document and receipt for them then make distribution to appropriate sections and again repeat the page inventory and had the receiver sign for the document. It was a sad tragedy at times reading about the many casualties we suffered in field locations. I felt as if my finger was on the pulse of the war effort, and it was at times not pretty or pleasant knowing what was happening out there.

The enemy was not as ineffective as they were made out to be. In one of these classified reports, I recall reading that different American units in totally separate areas of Vietnam were encountering enemy deceptive radio practices with the enemy posing as Hispanic-American soldiers. These enemy soldiers would somehow gain access to our radio frequency then send a call normally at or past midnight asking perimeter guards how many men were at their sector so they could bring them sandwiches and snacks. The enemy voice was always reported to have a Hispanic accent. In none of the cases I read did any American reveal the count of personnel in their sector; however, the fact that the enemy had gained access to our radio frequencies was daunting.

My access to classified documents provided me a clear picture of the whole war effort in Vietnam. Individual soldiers from generals on down were provided only that information for which they had a need to know, so most would have a narrow view of the war effort. My need-to-know was unlimited since I was required to inventory and account for each document page by page. This was, perhaps, a case where too much casualty information began to take its toll on the soul of a young twenty-year-old. It was perhaps here that my desensitization began to take form. My assignment at USARV would turn out to be a mild prelude to worse things to come in subsequent combat tours with Advisory Team 99 assigned to the 25th Vietnamese Infantry and with Advisory Team 51 assigned to the 21st Vietnamese Infantry Division prior to my final Vietnam assignment to the 101st Airborne Division and Project 404, Laos, a couple of years later.

Camp Alpha front gate and hooches

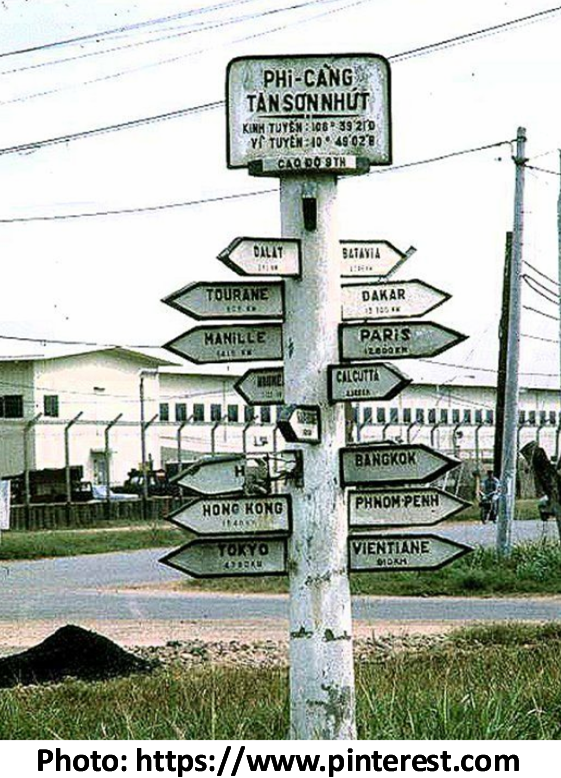

Welcoming sign at Tan Son Nhut Airbase Terminal

1 - Listen, Ojeda. Maybe these dumb asses forgot about us.

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022