I was busy repairing burnt cylindrical glass fuses to use on R-390 High Frequency Receivers which our data collection teams used to intercept enemy radio traffic. I overheard Staff Sergeant Ball (a Waco, TX, native) asking Sp5 Boyer to see what he could do with two captured Communist Chinese receivers and transceivers which a Sergeant First Class Bonnot whom I’d never previously met brought into our shop. The plan was to use these enemy radios to capture enemy radio traffic which our data collection teams would evaluate for military intelligence and pass on to 101st Airborne for target identification, maneuvering and defensive and offensive strategies.

Cylindrical glass fuses are actually designed to be replaced when blown and were never intended for repair. Replacing fuses with other than the specifically required amperage ratings ran the risk of burning up the equipment; however, desperate needs require desperate remedies, so I was willing to take that risk. We had several of these receivers already deadlined for the same fuse, and the fuses were not readily available through our supply channels. Critical parts being on order never solved a data collection mission, so I looked for other ways. Soon enough I discovered that a cigarette lighter applied to the metal end caps of the glass fuse loosens the glue allowing the metal caps to be removed intact. That done, I would take one or two single strands of wire (depending on my unscientific amperage guesstimate) from any electrical cord to insert into the glass cylinder. I would replace the metal end caps and again apply heat to reset the glue. This unauthorized method of repairing burnt fuses kept our data collection teams operational providing valuable enemy radio traffic.

Mitch Boyer had an abrasive personality and exploited the fact his father was a full Colonel within the Army Security Agency. When I first joined the 101st Airborne, I was assigned to troubleshoot several radios previously deadlined by Mitch for parts not available. Of some eight radios deadlined by Mitch, only two or three were properly diagnosed and deadlined for the correct parts unavailable at that time. I repaired the other of these radios with parts already available. Mitch never developed acceptable troubleshooting skills and would purposely deadline equipment for parts he knew were not readily available.

Mitch threw a fit when SSG Ball asked him to see what he could do with the two captured enemy radios. “I’m not going to work on these damn things. They have not been screened by the Military Police or Military Intelligence, and they might just be booby-trapped!

“I’ll wind up killing you and me and everybody in this place if you make me work on these damn radios. No. I will NOT mess with these damn things!”

I could see clearly SSG Ball was embarrassed at Mitch’s outburst in the presence of SFC Bonnot. SSG Ball turned to me and asked me if I could look at them. I agreed then Mitch yelled out at me “Well, you’re not going to work on them in this area cause they might be booby-trapped, and you end up killing all of us.”

Ignoring Mitch, I took them to the center of the small work area and proceeded to disassemble the radios gently, cautiously and with extreme care looking for anything suspiciously indicative of booby traps. Mitch left the area and returned from the Bat Cave1 some two hours later.

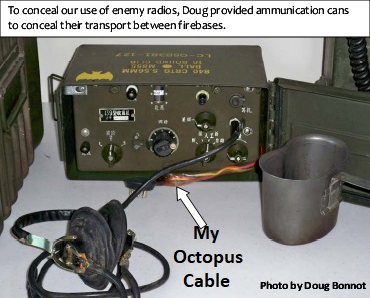

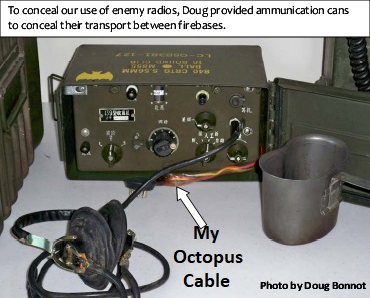

Meanwhile, I found that all the markings on the front panel and internally were in Chinese characters, so I went on instinct trying to decipher the circuitry. All voltages were in Arabic numbers, so I was able to determine all the required voltages in each of the circuits. The batteries, too, had their voltages indicated. As Doug Bonnot details in The Sentinel and the Shooter, I found suitable friendly batteries used in our military equipment to power these captured radios; however, their connectors were different from the captured radios. Using spent enemy batteries, I removed their connectors to fabricate the “octopus power cables” so named by the data collection teams because of the several different connectors required to power separate areas of the captured equipment. To keep our operators from accidental transmits, I located the transmit relay by keying and unkeying the transmit button several times. Once I located the transmit relay, I unsoldered its legs thus disabling the transmit mode leaving it permanently in the receive mode. This was critical to protect our operators from accidentally keying the transmitter and being located by direction-finding enemy personnel.

My modified captured radios were issued to our data collection teams. I learned from data collection team members that these worked beautifully since they were identical radios to those of the enemy and were totally compatible to the frequencies scanned by our data collection teams. The teams would not even use the long whip antenna which I had adapted for use. They would hook up a wire to the antenna terminal then tie the other end to the perimeter concertina wire. This gave them better-listening capability than the most expensive U.S. military radios in our arsenal.

Since no one else was willing to work on captured enemy equipment for fear of bobby traps, I became the SME (Subject Matter Expert) on captured enemy electronic equipment. Business was good as I kept getting an increasing number of captured radios to work on. I quickly developed a good stock of available parts from damaged radios which I used for cannibalization. I once received a captured Russian pocket transceiver with throat microphone which I was unable to adapt. Unlike the Communist Chinese radios, this transceiver had no operational voltage markings. If it were operational simply needing battery power, I probably damaged it by applying different voltages in an attempt to determine its operational voltage. I had visions of making this Russian transceiver operational allowing our Russian linguists to capture Russian radio transmissions. That did not come about. I marked that a loss in my win-and-loss tally.

Doug Bonnot was our Intelligence Analyst with 265th Radio Research Company, 101st Airborne Division. After retirement, Doug founded a multi-million-dollar company manufacturing military and specialized antennas. He also founded the Sentinel Chapter of the 101st Airborne Division Association and has been chapter president since its inception. I recommend Doug’s book available from Amazon since it’s an unadorned and factual book with real persons, real events and a telling account of the US Army Security Agency in Vietnam while operating as the 265th Radio Research Company.

Assignment to 101st Airborne Division was to be my third Vietnam tour. As stated in Doug’s book, the 265th Radio Research Company was the cover name for 265th Army Security Agency. It adopted its cover designation when the unit deployed from Ft Campbell, KY, to Vietnam in 1967. The cover designation was designed to mask the fact that the Army Security Agency was operating in Vietnam. Secondly, the cover was an attempt to make our company blend in as a non-descript Regular Army unit since our intelligence-gathering mission made us a very high priority target. Doug Bonnot details in his book The Sentinel and the Shooter how our mission was so classified that we could not receive general anesthesia without an assigned escort. Every member of the Agency had a statement in his medical records requiring an assigned Agency escort before any anesthesia for medical treatment would be provided except in cases of emgergency.

I joined them in 1970 and spent thirteen months with them working out of Camp Eagle near Hue and traversing the many firebases around the northern I Corps in which the 101st Airborne Division operated. Our 265th Radio Research Company was one of the most decorated units in the 101st Airborne Division and included several Vietnamese Crosses of Gallantry with Palm and others without Palm. While it was designed to be awarded only at the company level and above, exception to policy was granted and the Presidential Unit Commendation was awarded to one of our platoons for some very valuable enemy information collected in over-the-air radio monitoring operations.

In June or perhaps July 2003, I was back to Fort Campbell, KY, home of the 101st Airborne Division, to attend the first-ever reunion of the 265th Radio Research Company. Doug Bonnot interviewed several of us whose names were in his Vietnam notes. In a few brief and seemingly insignificant statements, I answered Doug’s questions about the captured radio modifications and adaptation, the “octopus cable” and ammunition cans. Seven years later Doug Bonnot’s book was published.2

Communist Chinese Transceiver which I would modify for our use.

1 Bat Cave was our company club we build from plywood, screening material and corrugated metal roof. Cheap beer was always available before, during and after work.

2 The Sentinel and the Shooter details U.S. Army Security Agency operations in Vietnam with the 265th Radio Research Company, 101st Airborne Division.

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022