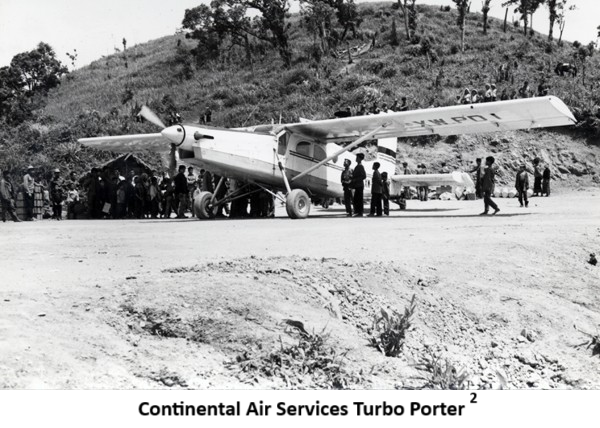

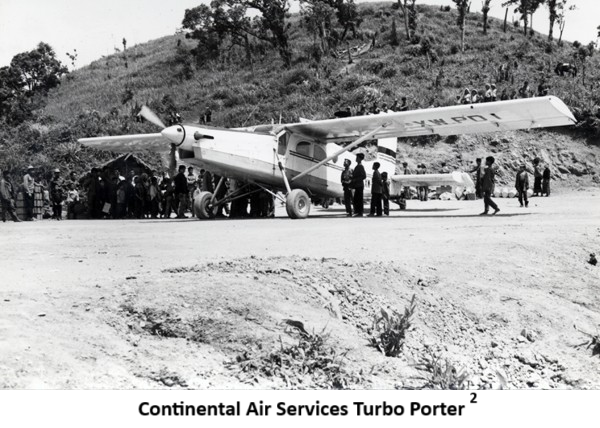

I left Vientiane on a Porter STOL1 flying to the Long Tieng CIA base somewhere in the northern mountains of Laos occupied by Hmong tribes. It was a base in the midst of a mountainous range where the airstrip was minimal and took a skilled pilot to drop the aircraft as close to the start of the airstrip, reverse the engines and just as quickly apply full brakes in time to stop the aircraft before reaching a massive rising mountain column at the end of the airstrip.

I dreaded flying into Long Tieng in a C-123 or C-130 sitting in the front cabin bench behind the pilots, but a Porter was pretty much of a routine landing with all the landing drama, fear and anxiety removed. Flying in a C-123 Caribou or C-130 Hercules was a totally unnerving experience. As soon as we touched down, the rising column at the end of the runway would start looming, and it was a tossup whether we would completely stop the aircraft in time or burn in a fiery crash upon hitting the mountainous wall. Two T-28 trainers and one C-123 which apparently were unable to make the required stop in time were left there in pieces on the side near the end of the runway - monuments to the necessary landing skill required to negotiate the treacherous landing.

I always carried paperbacks to occupy my flying time to the many remote sites. I had amassed a collection of better than half of John D. MacDonald's Travis McGhee series books. I was drawn to the Travis McGhee series when I first picked up a copy of "Dress Her in Indigo" where McGhee is overnighting in Brownsville, Texas, and clearly and accurately describes motels and key points in Brownsville along Highway 77 near my hometown. To me, Travis McGhee became more than a fictional character.

Only as we approached the landing strip did I pull away from my book to take a good look at the passenger on my aircraft. He appeared to be in his mid-forties, wore a completely black uniform with a black Fedora. I had heard about this Catholic Father from some of the folks I worked with, so I quickly surmised this was him. I helped him load his bag onto a jeep that was waiting for us, and we talked briefly. He was from somewhere back East and had been working with the local Hmong tribes in Laos for several years.

The Father would visit the Hmong tribes and conduct traditional Catholic services. He asked me what I did. I lied. I lied to a well-intentioned Catholic Father. He probably knew what my mission actually was, but he graciously accepted my lie that I was there to visit a friend. I asked the jeep driver to drop me off by a communications metal hut with a whip antenna rising above the roof. I off-loaded my two Samsonite suitcases specially built to carry my radio equipment and bid goodbye to the Catholic Father.

I found Mark in his communications hut. He told me his problem with the radio equipment. I quickly determined that was something more serious than a field fix. It would require diagnostic equipment available back at our Vientiane maintenance facility. I switched out the radio with a known good one I brought and made numerous radio checks with Vientiane, Savannakhet and Luang Prabang to insure we had reliable communications. My job done, I offered to monitor his radio systems for him while he took a well-deserved break. Mark was gone mere minutes and rushed back asking me to get to Air Operations immediately since there was a direct flight to Vientiane getting ready for take-off and agreed to wait for my arrival.

On my flight back to Vientiane, I kept thinking about the Catholic Father who was serving the Hmong tribes. He was there without any form of protection other than God's and the Hmong tribes he served. I had foolishly asked him if he carried any weapon or any other defensive means. "No need. I put my faith in my Lord," he said.

On a subsequent trip to Long Tieng, I again saw the Catholic priest in Hmong country. He greeted me with a smile, asked me how things were but never stopped long enough to hear my reply. He seemed more comfortable with the Hmong tribes than with Americans. Strangely and for an unknown reason, this Catholic priest stuck to my mind. "Why did he choose to minister to these people in an environment fraught with danger and hardship?" I asked myself. The answer is pretty obvious when you apply the Catholic doctrine. The Roman Catholic Church teaches that the poor represent those who are marginalized in society. Jesus himself taught the importance of helping those who are poor and need help. The Church also teaches about the 'preferential option for the poor', that in order to improve life for the poor, we should speak for the voiceless and defend the defenseless.1

I never ran across any other priests during my thirteen months in Laos. I kept thinking that Catholic priests are perhaps picked for the most remote and difficult regions of the world to serve and convert indigenous folks while Methodists, Baptists and Jehovah's Witnesses cater to the safer, more populated regions of the world. I found this to be an interesting and profound observation that certainly elevates the Catholic mission above all others.

1 https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z4g9mp3/revision/4

2 Porter STOL photo courtesy of Dr. B. R. Lang who was Deputy Army Attache, Laos

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022