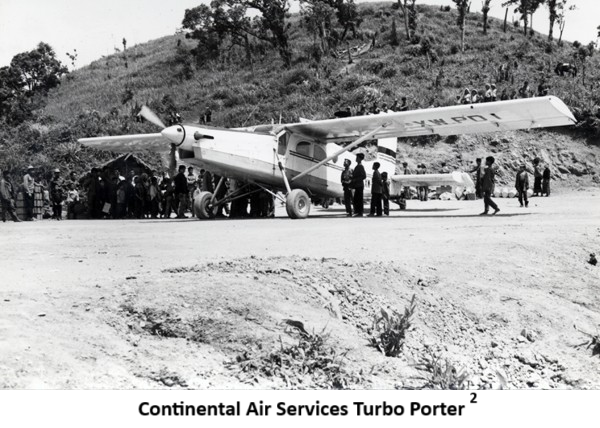

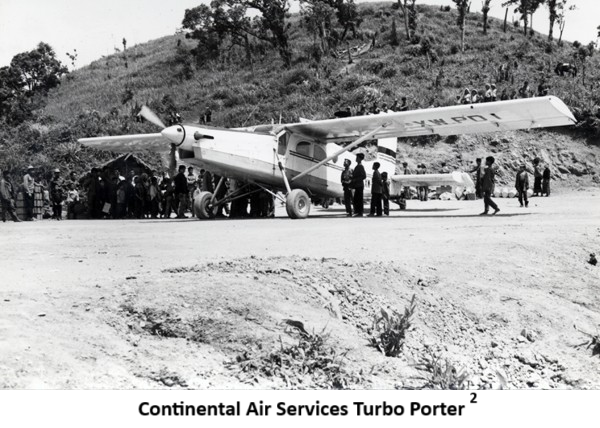

I was flying on a mission to install a communications system in a remote outpost near the Plain of Jars in the northeastern area of Laos. There was a two-man team there in military fatigues bearing no rank or unit identification. They had no commercial power and were totally dependent on radio batteries for emergencies and on a one-kilowatt generator which they operated for scheduled communications checks with Tiny Tim.1 Don, my US Air Force counterpart, drove me to the Vientiane air operations office where we learned the Continental Air Services Porter reserved for my flight would not be flying for another hour or more. The assigned pilot had been diverted to another flight and air operations was hastily trying to find an available pilot to fly my assigned Porter. We were given the tail number for my Porter and directed to stand by the Porter until a pilot was found. I asked Don to drive us to the flight line where my Porter was parked.

I was loading my equipment onto the Porter when a Laotian walked up to me asking in broken English, “I fix generator. You go, too?” Even by Laotian standards, he was a smallish Laotian of perhaps five feet wearing the traditional Project 404 dark navy blue uniform designated for Lao maintenance personnel. He seemed quite nervous as we stood by the plane waiting for the pilot to arrive. My suspicious nature began to surface as the Laotian kept opening and closing both his toolbox and a cardboard box two or three times before the pilot arrived. I asked him to show me his toolbox and the cardboard box he had with him. Since the flight had been assigned to me, I had control of passengers, cargo, destination and departure times. He opened his toolbox and cardboard box, and I found it to be the normal range of mechanic tools and some type of repair parts.

The pilot arrived and began doing brief pre-flight checks. I spent a few minutes briefing the pilot on my assignment and approximate duration time I expected to be on the ground at destination. I asked him if he had ever flown to my map coordinates. "If it's not a built-up area, I have not been there. I fly only into the built-up areas. Tell me more about this place in the sticks you're going to."

"It is actually way out in the midst of a wooded area, but there's an old abandoned French dirt airstrip nearby," I replied.

"I'm sure we'll be just fine," he replied. "Just be patient. I've been flying in-country only a few weeks."

"And where were you flying before here?" I asked. I was beginning to have an uneasy feeling with this guy.

"Oh, I've flown all over central Georgia. I own a crop-dusting service in Georgia. That's where I learned to fly. But flying is flying. One just has to get used to a new set of controls."

The Laotian and I both climbed in the back and buckled up. As the plane started going down the runway, the Laotian seemed even more nervous. I suspected at that point that this must be his first airplane ride. As we taxied down the runway, he kept looking out the window then turning to me and grinning. I removed my headset to hear what he was trying to tell me, but the roar of the engine was overwhelming. I could not hear. As I felt the plane lift off the ground, the Laotian got overly nervous then grabbed my knee and began squeezing it hard. My first thought was to slap his hand off my knee, but then I realized he was just scared stiff. I let him have my knee. As the plane reached flying altitude and leveled off, the Laotian let go of my knee and seemed to just go limp and relax. He turned to me and smiled. I ignored it and just kept reading a paperback I always carried with me.

Upon landing at the remote site covered by tall, beautiful pine trees, I spotted a civilian jeep waiting for us at the end of the dirt airstrip. The pilot's job was done for now. He stayed with the plane until generator man and I returned. The American driver helped us load the equipment onto the jeep and drove us deep into the wooded area where the other American was waiting. The two were living in a two-room block building unadorned and bare walls. The entire outer perimeter of the building was littered with leftover cement blocks and other building materials.

"One of these days, these locals are gonna have to get their asses back here to clean all this shit they left behind," the driver said as we pulled up to their block building.

Wasting no time, the Laotian and I set about to complete our mission in minimum time. The Laotian knew his business. He practically rebuilt the generator and had it working in less than the four hours I spent setting up my communications system. Once I made every conceivable radio communication check with Tiny Tim1 and other near and far command centers, I packed up my equipment onto their jeep and had one of the two Americans dressed in military fatigues wearing no rank, name tag or identifying markings drive us to the landing strip. He asked if we had room for another person. I informed him we had an extra seat.

"Look, the other guy’s had a bad case of diarrhea for about three days now, and we have nothing here he can take for it,” he said. “I’m trying to make him go back to Vientiane and see a doctor, but the dumbass just doesn’t wanna go.”

The Laotian and I loaded all our equipment onto the Porter. I asked the American to go back and get the other guy so we can take him to Vientiane. He was back in less than twenty minutes. Diarrhea man was still complaining about leaving saying “Look, what are you going to do by yourself? I can’t just leave. Now that we have operational radios I’ll just contact Vientiane and have them send me some medication.”

He didn’t want to leave the other team member all by himself in the remote outpost, but the wiser team member prevailed. “Just get on the goddamn plane and get your ass back to a doctor,” he said. “I’ll be fine for a day or two till you get back. Besides, you’re pretty fucking useless to me like this!”

We all boarded the plane and had an uneventful flight back to Vientiane. The Lao generator repairman was now a seasoned flyer and had no need for my knee. Diarrhea man got to the doctor without incident.

I saw the two Americans in an embassy function some weeks later. The wiser of the two had been drinking hard and was loud and boisterous. He saw me from across the room and came over and grabbed me by the back of my neck shouting to no one in particular “This man … this man … he saved my life! He flew to our outpost and gave us radio communications with Vientiane. He also saved my partner’s life! He brought him back here to see a doctor.”

I was somewhat embarrassed, but I could not break away from him without making a scene. Just then, diarrhea man walked up to us and removed the guy’s hand from the back of my neck telling me “Excuse him. He’s had it rough the last couple of weeks. But he really means it. Thanks for helping us out. We really appreciate it.”

I acknowledged his appreciation then left to join my own group of friends thinking how sad it is when it takes alcohol to express gratitude. Without the generosity of an abundance of alcohol provided by a free bar, I would've probably never have known that these two guys really appreciated my efforts and my contribution to their operational mission. No one ever revealed the nature of their operational mission. I can only speculate, but it was a highly classified mission.

1 Tiny Tim was codename for the main communications center for Project 404. All operational missions throughout the Kingdom of Laos were coordinated with and reported through Tiny Tim.

2 Porter STOL photo courtesy of Dr. B. R. Lang who was Deputy Army Attache, Laos

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022