Mark called me by radio telling me his equipment at Long Tieng had become intermittent and could transmit mostly only during the day. That was a sign the transmitter or amplifier had degraded or the antenna was cut to the wrong frequency.

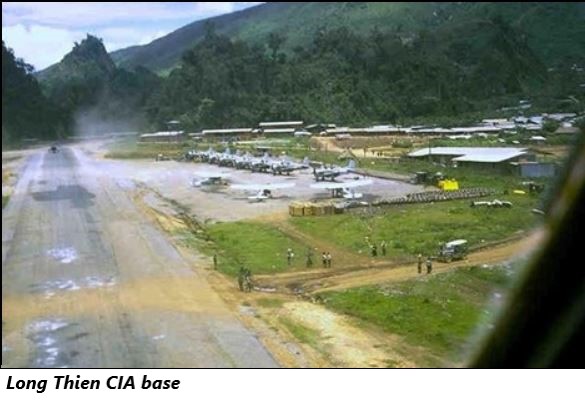

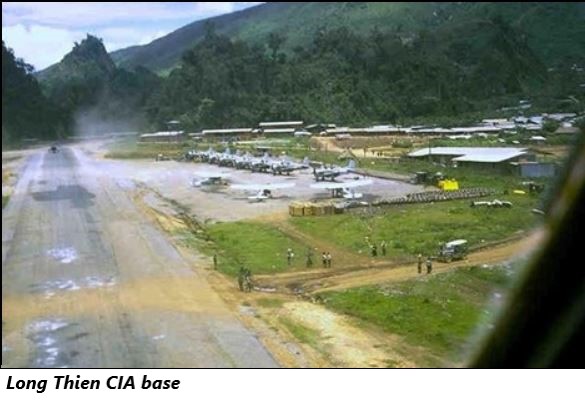

I picked out and tested a transmitter and amplifier off the shelf and packed a couple of cobra-head antennas to replace the ones on-site. We used specially-designed Samsonite suitcases to transport our equipment to field sites. This was a feeble attempt to hide the fact that we were in the radio communications business. I flew in to Long Tieng, the CIA camp situated in the northeastern mountainous area, in a C-1301 which was delivering a bladder of fuel. The aircraft departed only minutes after unloading its fuel bladder. It would never stay on the ground any longer than required due to its value as a target.

I knew I'd have a difficult time making it back to Vientiane. I found Mark's equipment to be working just fine but replaced the transmitter and amplifier nonetheless. Mark helped me take down and check the cobra-head and found evidence of moisture coming out of it. I had already wasted some two hours. Mark assisted me in taking down his antenna and replacing it with a new cobra-head using his same antenna lead. Fortunately, his antenna lead was long enough that I was able to reuse it after replacing the connector end.

Mark had a lot of teletype traffic to transmit, so I left him there to begin my return trip to Vientiane. I stashed all my equipment in my specially-built Samsonite case and set out for the air operations shack. Even with a steady stream of flights coming and landing at the airfield, there was no direct flight to Vientiane, so I just sat there and waited.

There was a mess hall operated by the CIA folks with local Hmong cooks who had been trained to prepare a range of American dishes from steaks to meatloaf to pasta. I learned from the air ops folks they were serving meatloaf for lunch. I left my suitcase in the care of the air ops folks and set out for the mess hall where I had a respectable plate of meatloaf with veggies and rice with ice cream and a chocolate cake.

CIA pilots would bring in American foods from Na Kong Panong or Udorn in Thailand. They had a fabulous food resupply system in this remote mountain camp. Leaving the mess hall, I began walking towards the air operations shack when someone in a jeep stopped to give me a lift. I told him I was trying to catch a flight to Vientiane but was not having much luck. He told me of a Porter leaving in the next few minutes. There were still no direct flights to Vientiane, but he suggested I take the Porter STOL2 headed to another location where I could then catch a flight to Vientiane.

I left on the Porter to an unknown destination. Upon reaching that destination, there was a UH-34 Air America chopper headed in the direction of Vientiane. I boarded. In-flight and not long after boarding, I was on the headset and learned our flight was being diverted to pick up pax (passengers).

"How many pax?" the pilot asked.

"Two pax. Body bags," came the reply.

"Roger, out," replied the pilot.

The body bags were loaded and secured. One of them was pretty much flat because it had apparently been sufficiently decomposed. The second body bag had some bulk to it. We stopped in an unknown location where the pax were quickly removed by two Americans. One of the Americans gently grabbed the first body bag on one end and the other on the other end. They handled the second one similarly. I recognized one of the two Americans as a regular diner at the American Community Association's dining hall, but I never knew what his actual job was. He asked if I were going to Vientiane. I nodded. Pointing to an Air America fixed-wing on the dirt airstrip getting ready to taxi out, he said "I can get you in that aircraft if you wish. It's headed to Vientiane."

He radioed the Air America fixed-wing. I boarded and continued my flight to Vientiane reflecting on my two pax. It was evident the pax were not fresh. Even in body bags fully zippered up, the signature stench of death was quite evident. It is a stench that lingers and invades every pore of your body. This was not my first time to experience the stench. I had experienced it while with Advisory Teams in Vietnam and was to experience it yet again in future episodes.

I silently prayed for the pax. They were American. Upon my return to Vientiane, I stashed the equipment in my room and took a long, hot shower trying to remove the stench that had permeated my clothes, my hair and every pore of my body and completely immersed itself in my brain, my mind, my being. Forty-plus years later I can still recall that pungent, heavy stench of death. I attribute that to airborne bacteria from the corpses being lodged into the nose hairs, and they multiply before finally disappearing slowly.

Many years later as I was readying for retirement from Computer Science Corporation, I assembled all my department managers for our last official meeting and mentioned I was leaving the following week for a "get well tour" to both Vietnam and Laos. After the meeting an employee who was waiting for the room to clear approached me and told me his Special Forces brother had been assigned to a Special Forces unit training the Montagnards3 in Vietnam. Every so often his brother was picked up by an Air America aircraft and flown to Vientiane with the mission of recovering US pilot casualties. He would be supplied with a motorcycle and given coordinates of where to look for the bodies.

In one particularly sad incident, his brother located a lifeless pilot in the midst of a thick forest. His parachute was caught up in a tree several feet from the ground. He climbed the tree, cut the parachute cords until the body fell to the ground scattering as would a watermelon falling to the ground. The uniform was badly damaged in the fall, but he was able to locate most of the insignia, dog tags and markings and place them in a body bag he carried. When done, he threw the body bag over his shoulder and hurried back to Vientiane where he returned the body to the US Army Attache's office. Unknowingly, I may have provided his brother's communications radio for him to stay in touch with Tiny Tim.4 Small world.

1 The C-130 Hercules is a four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings. It was originally designed as a troop, medevac, and cargo transport.

2 Porter STOL - Short Take Off and Landing aircraft.

3 Montagnard is French meaning "mountain people" and are indigenous to Central Highlands of Vietnam.

4 Tiny Tim was our communications center for Project 404. All radio and teletype traffic was processed thru Tiny Tim.

©Copyright texan@atudemi.com - January 2022